The basic principle behind this and other

option pricing models is that an option to buy or sell a specific

stock can be replicated by holding a combination of the underlying stock and cash borrowed or lent. The idea is that the cash and security combined can be fairly accurately estimated and their combined value must equal the value of the option. This has to be so, otherwise there would be the opportunity to make

risk-free profits by switching between the two.

Take a simple example, the aim of which is to find the value today of a

call option on a

common stock that expires in one year's time. The current stock price is $100, as is the call's

exercise price. To maintain clarity and avoid the complicating effect of an option's

delta on the arithmetic involved, imagine that an investor holds just half of this stock (that is, $50-worth) in his portfolio. The portfolio's only other component is a

short position in a

zero-coupon bond currently worth $42.45, which has to be repaid at $45 in a year's time.

Next assume that the value of the stock in a year's time will be either $110 or $90. From these two postulated outcomes several conclusions arise. First, we can value the call option in a year's time. It will be either $10 or zero. Second, we can value the portfolio. It too will be either $10 or zero. This must be so, since the value of the portfolio is the stock's value minus the debt on the zero-coupon bond. So it is either $55 minus $45, or $45 minus $45. The future value of the stock may be uncertain, but the value of the debt on the bond is not. Third, the alternative values for both the call option and the portfolio at the year end are the same. If this is so, then their start value must be the same as well. The start value for the portfolio can be easily calculated. It is $50 minus $42.45; that is, $7.55. So this must also be the present value of the call option.

From this basic building block of the binomial model comes the formula that the value of a call will be the current value of the stock in question multiplied by the option's delta (which, in effect, was 0.5 in our example) minus the borrowing needed to replicate the option. Using our example, the linear representation would be:

Call value = ($100 x 0.5) - $42.45 = $7.55

This is the single-period binomial model, so called because the starting point is to take two permitted outcomes for the stock price and then work back to find what this means for the present value of the option.

In the real world, however, a single-period model is not practical, hence the development of the multi-period binomial model where each period used to estimate the price of the option can be as short as computer power will allow. As the number of price outcomes rises by 2 to the power of the number of periods under review, the model is computer-intensive; a model using 20 periods, for example, would need over 1m calculations. Additionally, rather than using arbitrary stock-price outcomes from which to estimate the value of the option, the model takes advantage of the fact that, given an estimate of the rate at which a stock price will change, future stock prices can be estimated within a reasonable band of certainty using mathematical distribution tables.

The result is a model which produces options prices that closely mirror market prices. Furthermore, because the binomial model splits its calculations into tiny time portions, it can easily cope with the effect of dividends on stock prices and, hence, option values. This is an important factor with which the more widely used

black-scholes option pricing model copes less capably.

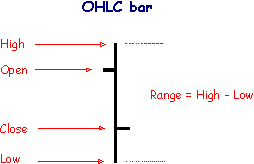

The most common type of price chart used to identify patterns that may give clues to future price movements in the investment under scrutiny. Price is plotted vertically and time horizontally. The price change for each unit of time - day, week, month, and so on - is plotted by a vertical bar, the top and bottom representing the high and low respectively for each period. Usually there will be a horizontal tick attached to the bar, representing the closing price. On the bottom of the chart more bars sometimes plot the volume of business transacted, scaled to the right-hand axis. This helps correlate price changes to volume of business done, which may be significant. For B example, a surge in the price of a share to new highs based on little volume could be a sign of impending weakness or, alternatively, a sign of strength if the buying has been done by informed insiders.

The most common type of price chart used to identify patterns that may give clues to future price movements in the investment under scrutiny. Price is plotted vertically and time horizontally. The price change for each unit of time - day, week, month, and so on - is plotted by a vertical bar, the top and bottom representing the high and low respectively for each period. Usually there will be a horizontal tick attached to the bar, representing the closing price. On the bottom of the chart more bars sometimes plot the volume of business transacted, scaled to the right-hand axis. This helps correlate price changes to volume of business done, which may be significant. For B example, a surge in the price of a share to new highs based on little volume could be a sign of impending weakness or, alternatively, a sign of strength if the buying has been done by informed insiders. instrument over time. Each vertical line on the chart shows the price range (the highest and lowest prices) over one unit of time, e.g. one day or one hour. Tick marks project from each side of the line indicating the opening price (e.g. for a daily bar chart this would be the starting price for that day) on the left, and the closing price for that time period on the right. The bars may be shown in different hues depending on whether prices rose or fell in that period.

instrument over time. Each vertical line on the chart shows the price range (the highest and lowest prices) over one unit of time, e.g. one day or one hour. Tick marks project from each side of the line indicating the opening price (e.g. for a daily bar chart this would be the starting price for that day) on the left, and the closing price for that time period on the right. The bars may be shown in different hues depending on whether prices rose or fell in that period.